Like some bizarre coincidence, you turn up at a museum, meet the exhibition’s co-curator, and as if by some power of mimicry, she could easily pass for one of the muses of the said artist. So it happened with Cécile Godefroy, co-curator of the major new show at the Picasso Museum in Paris, one that is destined to be a blockbuster: Picasso-Sculptures. And in case you were wondering, she resembles on more than one count that famous Woman Flower by the painter-genius from Malaga. If only Picasso were here to witness it…

First and foremost, though, Cécile Godefroy is an encyclopaedia of knowledge on her chosen subject. And that subject is itself superb. For a long time, Picasso kept the majority of his sculptures under wraps. It’s true that this great painter was obsessed by the idea of giving body to his creations, but more often than not he chose not to show the fruit of this research, or very rarely.

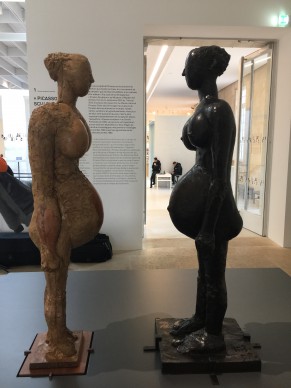

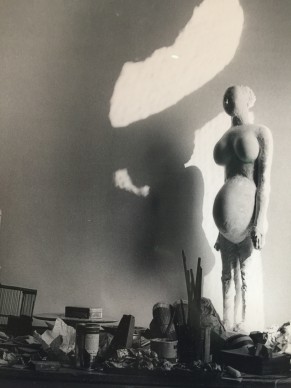

First it was MOMA in New York who between September 2015 and February of this year brought together Picasso’s sculptures in a sweeping survey. The show was a resounding success. Now it’s the turn of the Picasso Museum, which approaches it again with mastery but also with a more intellectual angle. It has to be said, the exhibition is sublime. The two first rooms of the Hotel Salé present the thesis: when it comes to sculpture, Picasso tended to work in series. The artist loved to surround himself in his studio with his sculptures. He created a kind of small, intimate theatre. They were his ‘domestic sculptures’ as the photos inside La Californie, his villa in Cannes, bear witness. Picasso studied materials, probed them, built with them, tampered with them and modelled them. This is illustrated in the first room through his Pregnant woman from 1950, shown in a photo taken in his studio, and then side by side in its plaster version and its bronze version. In the plaster version, he piles up terracotta crockery to form her breasts and her swollen stomach: jugs for the breasts, pitchers for the stomach. Picasso’s Pregnant woman is a primitive.

Another small room is entirely given over to what Picasso called a giant ‘Figure’, and it produces a powerful aesthetic emotion. It’s a unique piece, like a 3D drawing made of iron wires welded together into geometric shapes. There are the rigid black wires that up close make an abstract form but from a distance are a character; and then there are the shadows, which double the outline. Two knowing drawings in one composition. It was in 1928 that Picasso put the finishing touches to a system of welding with the help of his friend, the Spanish sculptor Julio Gonzàlez. Picasso paints his sculptures like in the Middle Ages. It’s the first time anyone did it in bronze in the 20thcentury, Cécile Godefroy informs me.

A room further on, which is certainly the apotheosis of this exhibition, is devoted to the sculptures he created in his studio in Boisgeloup, the castle he bought in 1930 and which is located at around 100km from Paris.

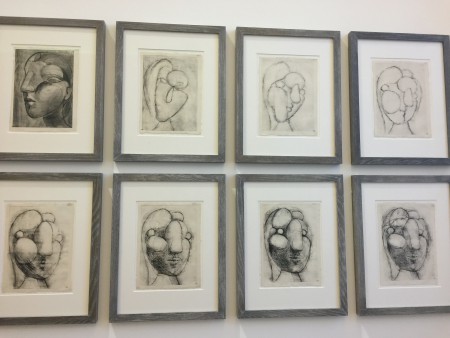

On 8 January 1927, as he was leaving the Galeries Lafayette department store, Picasso’s gaze met that of a young woman with large blue eyes. She was 17 years old and her name was Marie-Thèrèse Walter. He fell head over heels in love and 1932 was a year marked in his work by the apotheosis of his love. His subject is phallic, including the nose of the beautiful and hieratic young woman.

The room dedicated to the Boisgeloup studio is filled with the obsession of a painter who sees in 3D. Plasters, a lot of plasters, some of them never seen before – he’s fond of the this material’s whiteness – and drawings that were produced frenetically. A forest of Marie-Thèrèses, a hymn to the quest to give form to love. Picasso is a colossus.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.