If the role of art in your life amounts to concerns such as whether the painting in your living room matches the colour of your sofa then you should probably steer clear of the 57th Venice Biennale where the largest exhibition, the international pavilion, is ‘curated’ by Christine Macel. Born in 1969 she is Chief curator at the Musée National d’art Moderne in Paris also called Pompidou Centre.

She has assembled a show with 120 artists (103 of whom are showing at the Biennale for the first time) across the Giardini, the gardens created by Napoleon, and the immense Arsenale.

The marathon course is exceptionally rewarding.

Eschewing glamour, it is intellectually challenging at times, highly eclectic, full of surprises and unequivocally anti-commercial.

She explained the project in a few words (see too my report posted in February when the show was announced).

In fact Christine Macel is continuing in the great French tradition, both as an intellectual exercise and as anti-art market, but with a discernment that does her honour.

She’s opted not to place an artist at the centre of her major show by starting the exhibition in the Giardini with a statement – the artist has the right to do nothing – that is provocative to say the least.

More specifically, and it’s one of the keys of ‘Arte Viva Arte’ (the title of this 57th Biennale), the artist should not have to be a slave to his work.

‘For everything these days, erroneously, seems to revolve around the idea of money and work,’ Christine Macel observes.

One of the first striking images is of Franz West (1947-2012) the famous Austrian sculptor, having a siesta on a sofa he designed.

The rest of this huge exhibition (around 900 works in all) is like being led through the brains of artists and their obsessions.

One of the most beautiful rooms in the Giardini belongs to the acclaimed American artist Kiki Smith (born 1954). She has drawn large figures on Japanese paper. ‘I wanted to build a kind of chapel but also show the energy emanating from people,’ she explains.

Her neighbour, Hong Kong’s Firenze Lai (born 1984), produces powerful and colourful paintings in a new mix of expressionist and surrealist genre that conveys the sense of solitude in our great urban social circus.

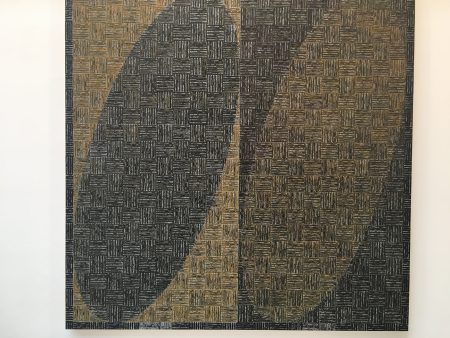

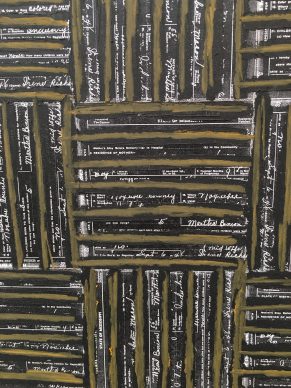

At first sight, McArthur Binion (America, born 1946) makes abstract paintings. But closer inspection reveals that they are a repertoire of his acquaintances through a mass of birth certificates, forming geometric, coloured figures.

At the Arsenale, the American-Taiwanese artist Lee Mingwei (born 1964) is staging a poetic performance for the duration of the Biennaleinvolves sewing together items of clothing (using a multitude of coloured threads) that he offers to mend for visitors.

It has to do with the beauty of human encounters.

Thu Van Tran (born 1979), a French artist with Vietnamese heritage, has made a magnificent wall in pink hues to hang her leaf paintings.

It’s not only aesthetic but also symbolic. The leaves are rubber plants from her country of origin and Brazil. The wall itself has been rendered with the same material. It’s all about the use of sap flows from this tree and its economic and political repercussions.

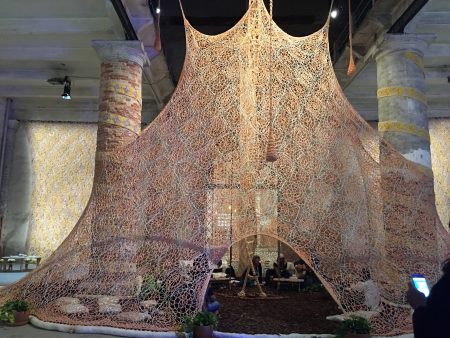

The most spectacular installation on display, this week at any rate, is by the Brazilian Ernesto Neto (born 1964).

He has designed an immense lace-like tent made from braided fabrics.

He wanted to show how contemporary man has cut himself off from nature, unlike the indigenous people of the Amazon. So this week, and this week only, under his immense and beautiful tent, a group of indigenous people from the state of Acre, on the border with Peru, are sitting in a circle, close to Ernesto, in a impressive calm, listening to music or gazing dreamily.

‘They know the teachings of nature,’ he explains.

I should add that the atmosphere is magical. At the centre of the installation is a ladder shaped like a snake. It’s the ‘mystical ladder for reaching nature’s secrets’.

Berlin-based Franco-Algerian artist, Kader Attia (born 1970) knows at least one of nature’s secrets.

In his installation he illustrates German physician Ernst Chaldni’s (1756-1827) discovery that the sounds vibrations make geometric patterns that also recur in nature.

Here, he makes highly sensitive couscous grains vibrate to the rhythms of the Middle East’s greatest voices. Fascinating.

Christine Macel succeeds in embracing a global world, a world that is curious, sensitive and open.

She blows hot and cold, with the poetic, the beautiful and the cerebral.

The visitor is treated to one discovery after the next.

It’s the main aim of the International pavilion of the Venice Biennale.

OUI : Viva Arte Viva!

Until 26 November. www.labiennale.org

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.