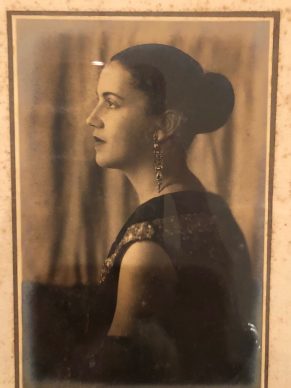

Take Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973). Does her name sound unfamiliar to you?

That’s understandable.

She presents two major disadvantages. She’s a female painter who was also Brazilian.

However, this wrong is beginning to be redressed with an exceptional exhibition dedicated to her at Moma in New York, showing until 3 June.

The exhibition’s co-curator, Luis Perez-Oramas, explains this international amnesia:

Tarsila, as she is familiarly known in Brazil, invented both a painting style and a world which were unique, a fusion of modern Western concerns combined with a Brazilian identity forged from diversity and haunted by a desire for post-slavery liberation.

This is what can be seen at Moma, which has succeeded in bringing together her major works from the period of the 1920s and ’30s. Thereafter, the artist – who was particularly preoccupied with communist ideals – saw her creativity limited.

Tarsila came from a bourgeois Brazilian family and, like all aspiring artists around the world in the 1920s, she was attracted by the spirit of the avant-garde that reigned in Paris. She visited the city several times.

It was there that she followed the tenets of Fernand Léger but also of some of the more minor cubists like André Lhote and Albert Gleizes.

She said that: “Cubism is the artist’s military service.”

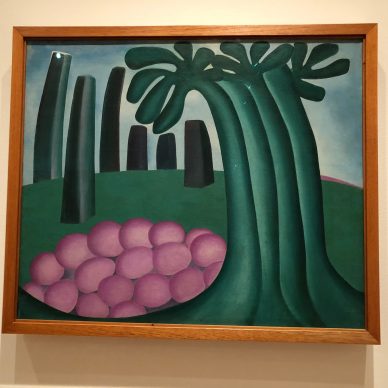

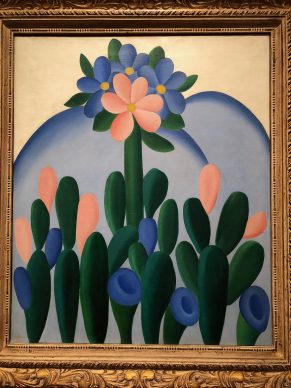

But Tarsila’s genius lay in the fact that she was not content to simply copy – even though certain paintings such as “Academy” from 1923 are very clearly inspired by Léger’s geometry. The colours are always vivid and contrasting.

The shapes in the landscape take the form of circles, rectangles and squares.

Most significantly, she distorts the bodies of the figures depicted in her paintings, which could be said to resemble a surrealist expression copying the effect of distorting mirrors. The choice of figures in her paintings also has a local flavour.

Luis Perez-Oramas explains -and that’s very important- how the concept of modernity doesn’t just have one European or Western origin.

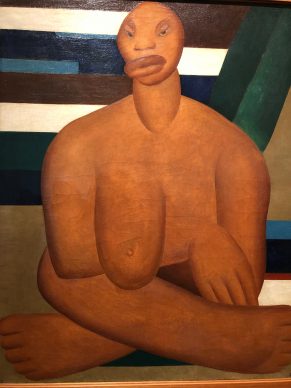

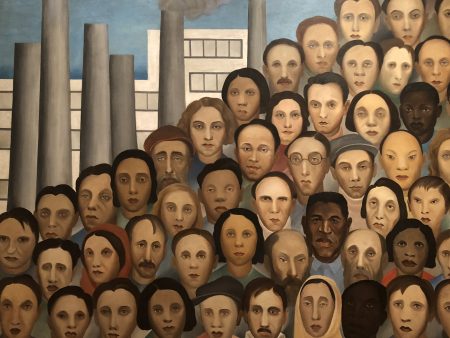

Slavery was only abolished in Brazil in 1888, and Tarsila had progressive ideas on the subject.

She painted those who were overlooked at the heart of society: the black population.

“A negra” from 1923 depicts a black woman with oversized limbs who literally invades the canvas.

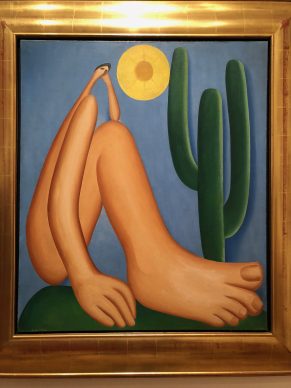

In 1929 the painting “Anthropophagy” makes reference to the “Anthropophagy Manifesto”, the theory developed by her husband at the time, the great writer Oswald de Andrade. The theory consists of symbolically reclaiming the cannibal practices of indigenous Indians, to literally make the substance of their enemies their own – colonialism, racism… – by ingesting it so as to draw strength from it.

Here the figures of paradise are naked and deformed in a Brazilian landscape with stylised forms.

In 1924 she painted “Cuca”, a strange creature which seems to be sitting like a human. Surrealism once more in exotic surroundings. She had the artwork framed by Pierre Legrain, one of the great French designers of the art deco period, as though to imbue this fantasy vision with extra value. The painting belongs to the French public collections.

It is hung at the entrance to Moma’s exhibition, as if to welcome visitors into the extraordinary world of Tarsila do Amaral.

Tarsila is a sort of surrealist-cubist version of Gauguin, who would have discovered her own Tahiti, the paradise she wanted her own country to be, by travelling to France.

Tarsila do Amaral. Inventing Modern Art in Brazil. Until 3 June.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.