This story was written after a trip to Saint Petersburg and Moscow

The history of modern art, in its great sweep, has been punctuated by miraculous tales of wealthy patrons who were more than just far-sighted, they were enormously generous towards artists who, thanks to their support, would majestically take flight.

In Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, for example, there was Gertrude Stein, the American who gave his backing to Picasso’s cubism.

In Russia, at the same period, two men fought over the territory of painting’s avant-garde. Their names were Sergei Shchukin (1854-1936) and Yvan Morozov (1871-1921).

The accidents of history, or more exactly the October Revolution and somewhat later Stalin’s repressive and dangerous spirit, have linked these two men together for perpetuity.

When in the 1970s both collections began to be shown again at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, visitors to these Russian museums have tended to speak vaguely about the ‘Shchukin and Morozov collections’ as if they were a couple.

You can hardly blame them, for the haul of modernist paintings which belonged to the pair at the beginning of the 20th century were shown with no regard for their different origins.

Yet each these gentlemen had quite distinct personalities, with Morozov generally considered to have more conservative tastes than his elder.

In Paris this autumn, the headline event is the arrival at the Fondation Vuitton, for the very first time, of 130 masterpieces solely from the Shchukin collection, one which like Morozov’s has belonged to the Russian state since 1918.

It brings together, for five months, a selection of the very best of the early 20th century avant-garde around the visionary figure of Sergei.

For many years the Russian authorities, fearing a confiscation order of this incredible collection from Shchukin’s heirs, have prevented exhibitions outside Russia. The exhibition at the Fondation Vuitton called for great diplomacy, the publication of a warrant prohibiting seizure, negotiations at the highest levels of power in both countries and a collaboration between two brothers with a long history of enmity – the Hermitage and the Pushkin Museum.

Shchukin was a Moscovite industrialist, a textile trader and the son of a textile trader, the third of ten children.

He had a frail appearance, he stuttered, and was so fragile that he was sent to study with a group of young girls. But as the old Russian proverb goes, ‘though the soap may be grey, it washes white’. In other words, appearances can be misleading. When his father died in 1890, it was Sergei who took over the reins of the family business. And made it turn a profit. He knew how to capitalise on the tastes of the new Russian bourgeoisie who prized fabrics with decorative patterns. In 1886, following the birth of his first son, Sergei moved into Troubetskoï Palace, a mansion in central Moscow. To cut to a long story short, this building would eventually be nationalised and is these days part of the vast Ministry of Defence complex.

Shchukin’s introduction to French art came with Impressionism. In 1897 in Paris, accompanied by his brother who was living in the French capital, he visited the temple of Impressionism, the Durand-Ruel Gallery. Sergei loved what he saw and snapped it up. His first foray into the genre was with Camille Pissarro, but he quickly graduated to the universe of the talented Claude Monet. In ten years he would purchase no fewer than thirteen works by Monet.

Mikhail Piotrovsky, the Hermitage Museum’s famous director, talks about Shchukin‘s unique personality

One of unique things about Shchukin was that all the paintings were bought with the objective of being shown in his house. He was determined to create a unique pictorial universe which he surrounded himself in and which he hung obsessively. ‘Shchukin was not limited by budget. His only limit was his wall space,’ explains Alexey Petukhov, the curator of French painting at the Pushkin Museum.

Alexey Petukhov, explains how Shchukin’s house was conceived as a museum:

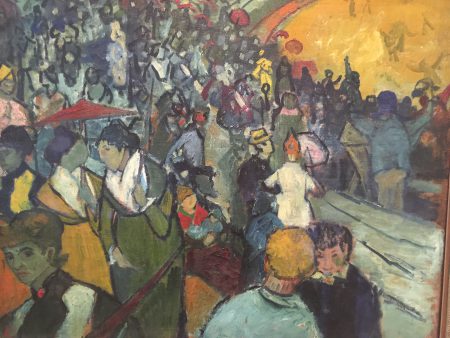

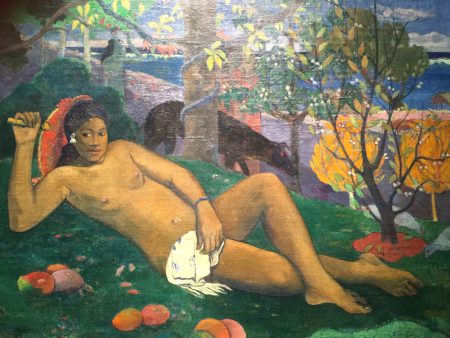

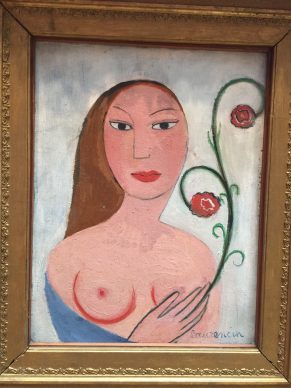

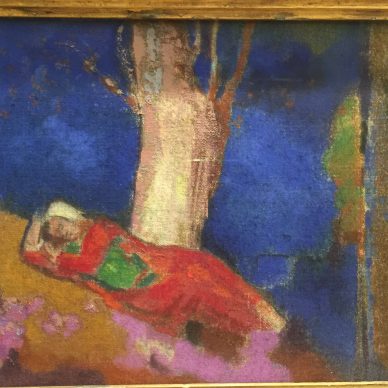

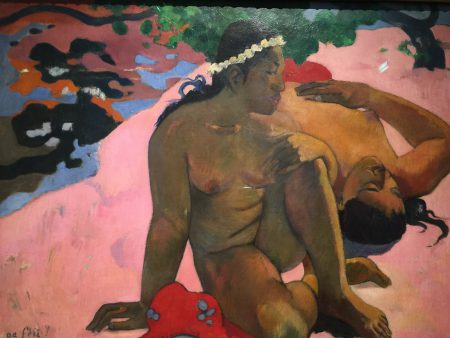

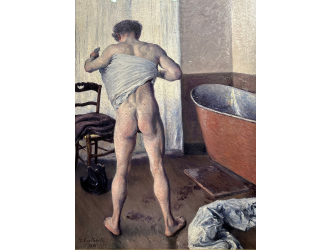

The most astonishing thing about the collector is the speed at which he took in the idea of modern art, the celerity with which he was able to accept a pictorial revolution that was then in progress. His last purchases date from 1914. By that time he had acquired 278 works, of which eight canvases by Cezanne, considered the father of modern art, as well as 16 by Gauguin are among some of the most beguiling.

Specialists believe that Shchukin definitively ‘switches over’ into modernism in 1905.

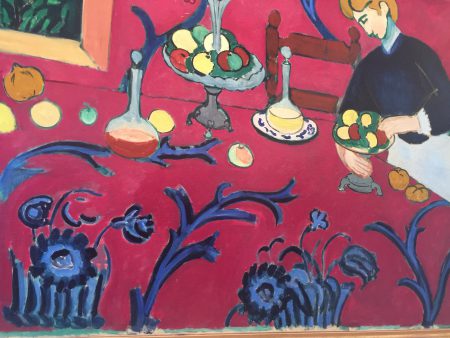

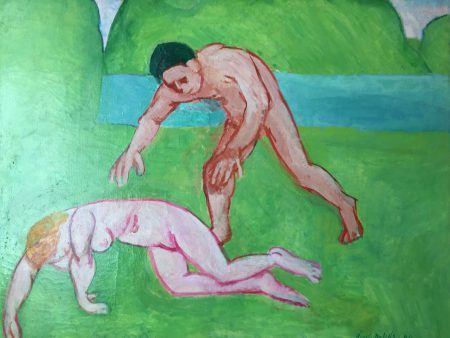

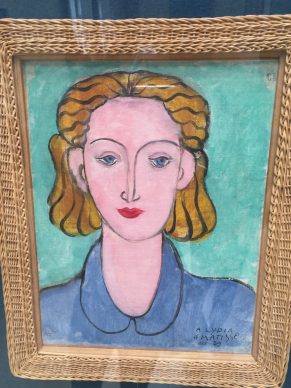

He has a particularly close relationship with Matisse, who he brought out to Moscow in 1911 to produce a work in his honour. The concept was colour.

The floor is covered in a violet rug. The walls are painted in green and the ceiling is pink. It is using this arresting multi-coloured framework that the French master hung his canvases. In total Shchukin would acquire 38 Matisse paintings.

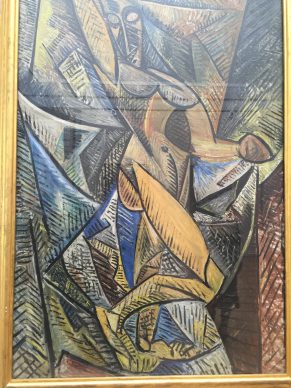

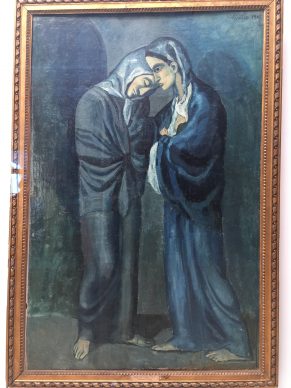

In 1907 the artist generously introduced the Russian collector to Picasso. Initially Sergei, visionary though he was, struggled to accept this new style of geometric forms to represent reality known as cubism. It would require two years before Shchukin was ‘prompted to act’ with Picasso. He would end up purchasing no fewer than 50 paintings by the Spaniard.

But he missed out on some big catches by his initial reticence. Albert Kostenovitch, the Hermitage Museum’s well-known modern art curator – among his accomplishments he published the Shchukin-Matisse correspondence – explains that when the Russian art lover saw ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ for the first time, a painting today in the MoMA and which is at the birth of cubism, the art lover simply took fright. Too primitive? Too iconoclastic?

Albert Kostenovitch discusses the diverse nature of Shchukin’s selections:

The general curator of the exhibition Anne Baldassari sums up Shchukin’s paradoxal attitude. ‘He worked against his own taste. He developed an ambivalent relationship with the works. He pushed himself right up to the edge of this vertigo in art.’

When the Bolshevik Revolution erupted, this very rich bourgeois left for Paris with his family, leaving behind all his possessions. Legend has it that managed to hide some diamonds in the head of his daughter’s doll. He died in France at the age of 81, his entire treasure in those memories of an idyllic palace named Troubetskoï and whose spirit is revived for the first time this October at the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

For Marina Loshak the director of the Pushkin Museum, there will be a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ the Shchukin exhibition:

The Shchukin Collection. Hermitage Museum. Pushkin Museum. Icons of Modern Art. From 21 October to 20 February. www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.