On 25 and 26 May, the fifteenth edition of Loop took place in Barcelona.

A one-of-a-kind fair devoted solely to video art, it takes an original formula for a genre that which is still finding its bearings. In a hotel in the city centre, 44 galleries each had a room where they showed 44 videos by 44 artists.

Video art finds itself in a paradoxical position today.

While the medium is ubiquitous at contemporary art shows, it continues to inspire a degree of mistrust among buyers.

The curator Caroline Bourgeois began assembling the video collection of businessman Francois Pinault in 1997.

She observes: ‘Today there’s a real market for video that can go up to 4 or 5 million euros for the best known names but is completely ignored at auction. In a way, investing in a painting carries fewer risks.’

One of the most worrying sides to the video market, for neophytes, is the ease of reproducing a work.

Christine Van Asch was a curator specialising in video art at the Pompidou Centre between 1982 and 2012.

She assembled a collection of video art stretching to 1,600 pieces featuring the biggest names in the discipline, from Bill Viola to Nam June Paik.

‘It’s simple, the market has the same rules as photography. There are limited editions and unlimited editions. And like with digital photography, you have to anticipate problems with conservation. That is why files have to be updated every seven years or so, at the same pace as technology advances.’

But as institutions have clearly understood, reproducibility also offers the advantage of being able to buy works jointly, with each party keeping a copy.

In 2012 a video that has become mythical, ‘The Clock’ by Christian Marclay, was bought by the Tate in London, the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

On 5 May the Pinault Collection and the Philadelphia Museum also announced that they were acquiring two recent works by US artist Bruce Nauman (born 1941), a pioneer in the genre, that one imagines to be worth several million dollars.

`

Among the most expensive works ever bought at auction there was a video installation by Bruce Nauman which achieved $1.6 million in 2016, but for other stars of the discipline like the South African William Kentridge or Nam June Paik, the figures do not exceed $650,000 at auction.

In Barcelona, the Galeria Senda director and co-founder of Loop, Carlos Duran observes how the reception given to the medium has changed.

‘Fifteen years ago the prices were timidly advertised at 2,000 euros. Today the average price at the fair is 10,000 euros.’

In his space he is showing a photo and video work about sports betting by Ana Malagrida (born 1970), a Spaniard living in France who in October was the subject of an exhibition at the Pompidou Centre. The two videos are offered at 5,000 and 7,000 euros.

What is most striking in the work shown today at places like Loop is the technical sophistication.

The most spectacular work at the fair, which incidentally received a Loop Award meaning it will enter the Macba Museum’s famous collection, was presented by the young Galerie Sator, located in the Marais, Paris.

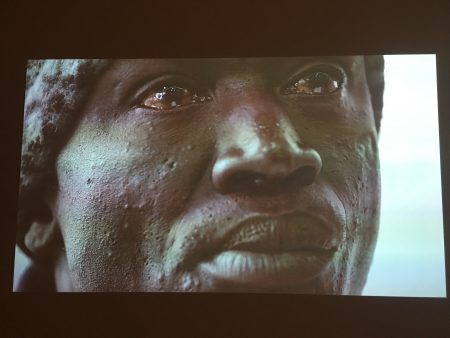

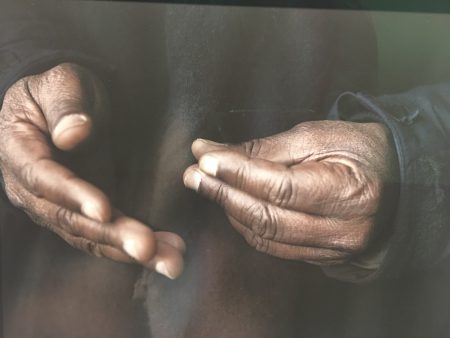

Across two large screens, images from ‘Ecstasy has to be forgotten’ were simultaneously shown. The work by Greek artist Evangelia Kranioti (born 1979) who is currently based in Paris is an oneiric double drift through Rio during carnival. It is limited to seven editions, is on sale for 8,500 euros.

(Me removed the video as the artist refused us to show an extract)

Among the video artists gaining wide international recognition is Frenchman Philippe Parreno (born 1964) who was the subject of an immense exhibition in the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern until 2 April. He had 6 editions on sale from his various gallerists for about 300,000 euros.

These days websites like Electronic Art Intermix (www.eai.org) and Bureau des Videos (http://www.bureaudesvideos.com) are offering videos by artists in unlimited editions starting from 25 euros.

The database Artprice indicates that video art accounts for only 0.3% of art market receipts across all fields.

It’s one more proof, if proof is necessary, that the contemporary art market is not a faithful reflection of current art production but only of its commercial interests.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.