Even though Andy Warhol may not have had the museum namesake he deserved in New York – only Pittsburgh accepted a Warhol Museum after his premature death – and even though he isn’t actually buried there – Pittsburgh again was the city of his birth, where he had many bad memories, and which is also home to his grave – he is still part of the local heritage in the same way as the Brooklyn Bridge or the Statue of Liberty.

There are many New Yorkers still living who knew him.

Warhol’s works and Warhol references have also long permeated the artistic landscape and the landscape of the art market in New York, as well as internationally.

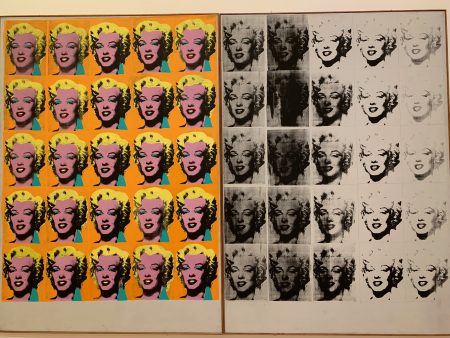

There is little in the Warhol attitude left to explore; the silkscreen print series and 15 minutes of fame have become well-worn and well-documented subjects.

I myself curated an exhibition on Warhol and television, Warhol TV, first in 2009 in France, followed by Portugal and Brazil, which seemed to me to be the only area about which relatively little was known of the genius artist, who died aged 58.

This is why, when the Whitney Museum in New York announced they wanted to stage a retrospective dedicated to the high priest of Pop Art, one might have had grounds to suspect that they simply wanted a blockbuster exhibition.

Having arrived at the museum armed with my scepticism, I must say that I was absolutely blown away by the show, which comprises 350 artworks from drawings to videos.

The director of the Whitney, Adam Weinberg, clearly explains the decision to feature Warhol in his museum’s program.

The exhibition was organized by Donna de Salvo, head curator at the Whitney, who has spent several years bringing this project to fruition.

In truth, the real question when it comes to Warhol is not “what’s new?” but rather “what’s good?”.

That’s not to say that everything in Andy’s output is bad, but to truly understand the artist’s approach one need to select the best of his work.

Warhol’s production is extensive, and Donna de Salvo has made an extremely specific selection. She explains, tactfully, what is good in Warhol’s work.

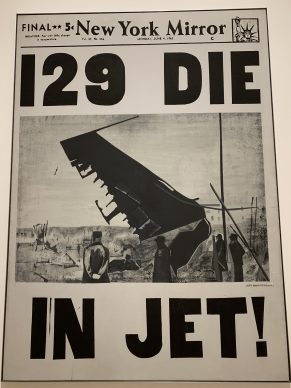

The early 1960s, a time of bubbling creativity, is the period that is particularly highlighted in the exhibition. We see, for example, an extraordinary painting made in 1962 which is a faithful yet hand-painted reproduction (and not using the process he later employed of silkscreen printing) of the photograph of a newspaper article with its title “122 Die in Jet” on the deadly accident involving an Air France plane.

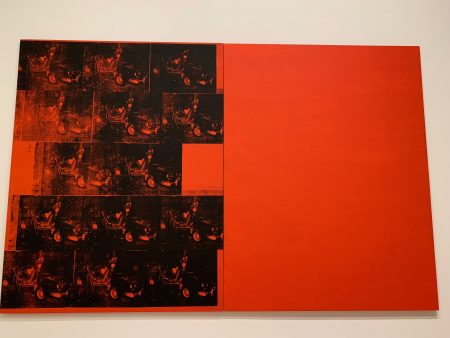

This is also the first painting from his legendary “Disasters” series, which demonstrates both Warhol and the media’s taste for the macabre.

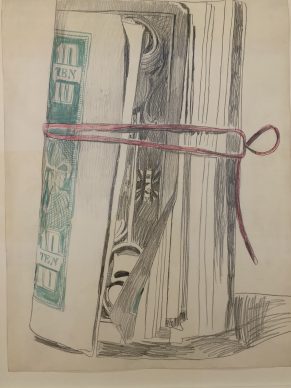

Warhol was a recycling genius, or in the words of 18th-century scientist Lavoisier: “Nothing is lost, everything is transformed.”

One of Andy’s most loyal assistants, Vincent Fremont, who is also a fount of knowledge concerning the artist, explains how Warhol never threw anything away.

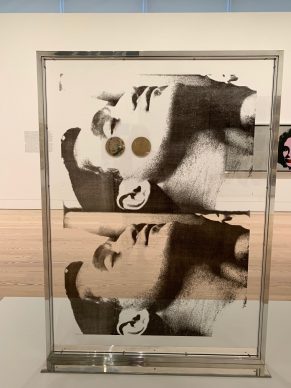

In the series of masterful acts of recycling, one of the exhibition’s great discoveries is an image printed in 1965 onto a specific material : plexiglass. Two years after filming the poet John Giorno in a state of eternal slumber in his famous work “Sleep” (this was Warhol’s “endless sleep” like Brancusi’s “endless column”), he took two images from the film which he printed in large format onto this transparent material.

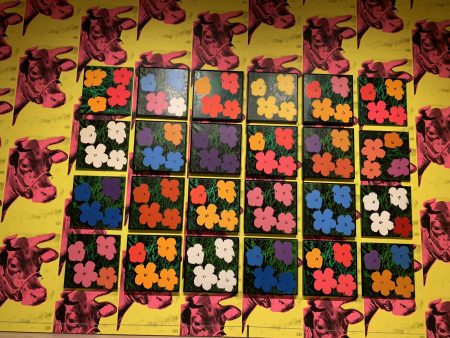

Over the past few years we’ve seen a flourishing trend in exhibitions lacking in imagination – which is to say, often – of featuring printed wallpaper that fills the space perfectly.

It was in 1966 that Andy Warhol, who was the first to do this, recycled the idea of installing wallpaper once used in the decorative arts in an exhibition at the Leo Castelli gallery, declaring that he no longer wished to paint. The fuchsia cows printed repeatedly against a garish yellow background have taken over an entire room at the New York museum.

Warhol’s latter years, however, have not been side-lined at the Whitney.

In this section, Donna de Salvo emphasizes the artist’s conceptual approach.

The most interesting thing about the work featured here is the artist’s confirmed flirtation with abstraction.

Bob Colacello, who worked for Warhol and his publication Interview magazine from 1970 to 1983, believes the artist actually wanted to branch out into all areas, including abstraction:

At the Whitney, the “63 Mona Lisa” created in 1979 in white on white is a great hymn to disappearance in painting.

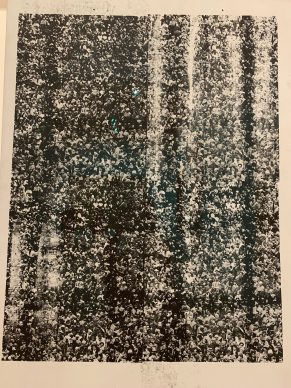

A year earlier he produced his huge “Oxidation Painting” depicting mysterious shapes in different shades of green, which – for those who didn’t know – was created from none other than the chemical reaction of urine poured onto a surface covered in gold metallic paint.

The label makes a reference to abstract expressionism. There is also perhaps a nod to Piero Manzoni’s “Artist’s Shit” from 1961 and, in an altogether earthier spirit, an allusion to a sexual act known as the “golden shower”.

Making the hand of the painter disappear then making the painting disappear or covering it in urine…

Warhol is a conceptual artist.

In the first-floor room, which is highly decorative and filled with portraits made by Warhol, all in the same format and more often than not for commercial purposes, the base of the portrait depicting Jean Michel Basquiat is another “Oxidation painting”.

The young painter who fascinated the Pop artist at the time may well have played a part in making it…

The title of the exhibition: “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” refers to his famous book dictated over the phone, “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B & Back Again”.

There’s a good quote in it, which takes the form of an evasive kind of conclusion, on the nature of good and bad art according to Warhol:

“Don’t think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide if it’s good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they are deciding, make even more art.”

Until 31march. https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/AndyWarhol

I cannot write this article without thinking with great emotion of someone who afforded me a detailed understanding of Warhol’s work, Tim Hunt. He was curator at the Warhol Foundation for nearly 20 years. He died almost a year ago in New York, on 26 November 2017.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.