Art which is political to the exclusion of all else is pointless, regardless of how human its message.

Art demands the foundation. It demands the form too.

Otherwise you simply end up with illustrations.

The greatest shock that I had the chance to experience recently in this harmonious marriage between an aesthetic and political work is on display at the Met Breuer in New York, the new annex of the Metropolitan Museum on Madison Avenue dedicated mainly to 20th century art.

It is currently home to retrospective of the American artist Kerry James Marshall (born 1955 in Alabama), which was previously in Washington and will be travelling next to MOCA in Los Angeles.

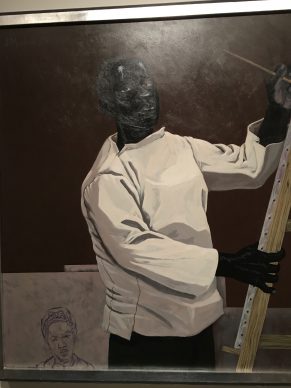

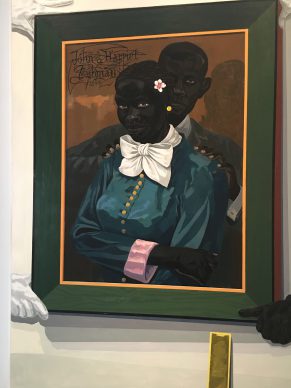

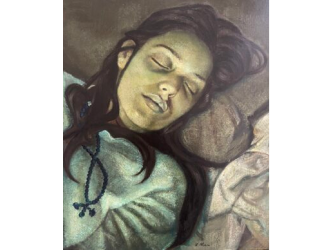

Marshall created a distinctive figurative style, luxuriant and highly colourful, peopled with completely black figures. The word black is often used to mean brown, but Marshall paints his figures dark black. They stop being people to become shadows.

He explained himself lucidly in an interview on the subject during his exhibition in Chicago:

Ian Alteveer, the curator of the exhibition, explains the concept of the colour used for the figures: ‘At the age of 14 he decided that he would paint his figures in black.’

It is here that the aesthetic joins up with the political project – to make that large yet ignored, transparent and inexistent section of the American population exist in Art.

Kerry James Marshall speaks about the ‘invisibility’ of black people. He refers to a book by Ralph Ellison published in 1952, ‘The Invisible Man’.

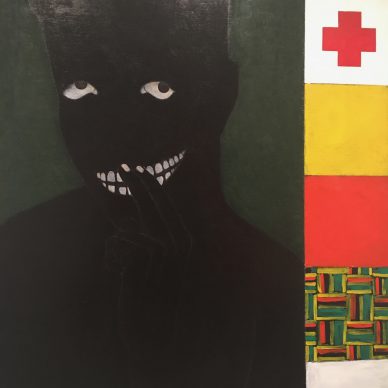

In 1980 Kerry James Marshall represented himself in black against a black background. Only his eyes, teeth and a bit of his shirt show through. He gives the drawing the conceptual title, ‘A portrait of the artist as a shadow of his former self’.

Ian Alteveer explains the objective of this exhibition, the first ever Kerry James Marshall retrospective:

If his younger years were given to making collages, later on in life he would turn to large format paintings. The exhibition is not hung in chronological order, and as a result the viewer struggles to understand the evolution of the artist’s style.

In his large compositions there is a quasi-theatrical atmosphere. They take up a concept that was particularly prevalent in 18th century Europe, the ‘genre painting‘ (scènes de genre), to produce freeze frames on images of contemporary life.

In 1993, for example, Kerry James Marshall depicted a barbershop scene.

Like in Matisse, the decorative motif is a key element. An arabesque of electrical wires, red furniture and white drawers, a pink basin, white tissue paper with a blue pattern, a black lino floor marked with white traces and writings everywhere.

The black characters come out even better on the three-metre canvas.

Marshall employs word games. He calls the painting ‘De Style’, a reference to the name of the barbershop but also to the Dutch art movement De Stijl, which played with colours, including in interiors.

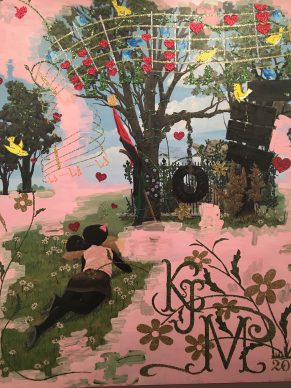

In ‘Watts 1963’ from 1995 Marshall paints the joy of a couple of young people in a park in Los Angeles on a 3.4-metre-wide canvas.

It’s apparently a reference to his family who moved with him from Birmingham to California.

Palm trees, lawns and small flowers punctuated with panels and banners. The bucolic scene is tempered, nevertheless, by the fact that the Watts neighbourhood was also the centre of violent conflicts between the black community and the police in the mid ’60s.

Don’t miss out on this chance to enter the rich and falsely enchanted world of Kerry James Marshall.

He pleases the eye but also makes an appeal to the history of art and the history of man.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.