The roots

At the root of art, you’ll find the roots of the artist. Many artists hold fast to their roots and their early struggles, transforming these experiences into creative fuel. Mark Bradford (born in 1961) is now a celebrated American painter. He represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2017 (See here a report about the Biennale 2017) and created an extraordinary installation of 32 canvases for the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. More recently, in September 2024, he was the subject of an exhibition at the Hauser & Wirth Gallery in Hong Kong, where he and I had the chance to meet. An exhibition of his work is currently on view through May 18, 2025 at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, offering a sweeping panorama of the past twenty years of his practice. (See here a report about a Bradford show in Porto, Portugal).

Without paint

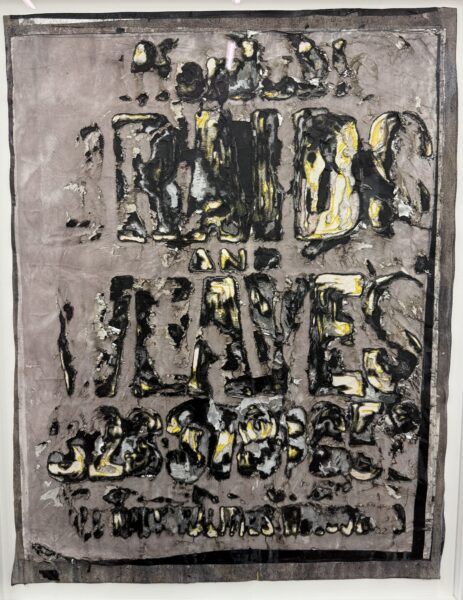

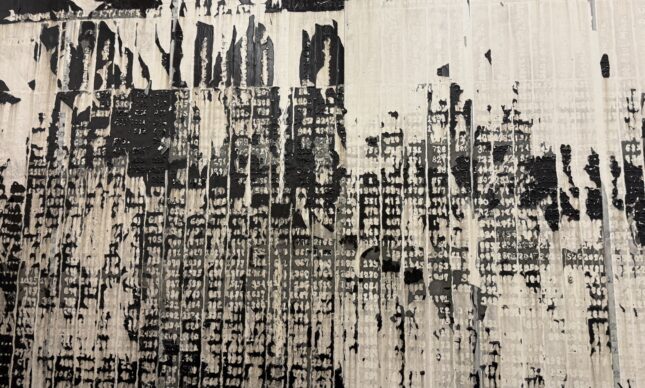

Here we see the evidence: At the source of his creative energies are his roots. Bradford has found countless ways to create abstract paintings, without paint, out of found materials. This was born out of necessity—he once could not afford materials, not even paint. The resulting works, often large-scale, are powerful. In Bradford’s art, what you see is not what you would think it is. “I’m working on two-dimensional surfaces. I feel like I’m engaging the history of paint. I’m inserting my work into that history, even though I’m not using paint,” Bradford explains.

Desolate Los Angeles

Mark Bradford. in Washington

This exhibition housed in a former train station ends—just like his show at the Venice Biennale—with a 2005 video titled “Niagara.” In it, we see a young boy, his back to the camera, walking endlessly through the cracked streets of Los Angeles. The boy could be Bradford himself—back to his roots in desolate Los Angeles.

Hair salon

So, let’s go back there. His story begins at his mother’s hair salon in Los Angeles. She styled hair for African American women, giving them chemical treatments using countless tiny white endpapers wrapped around strands of hair. “I started using these little endpapers […] from the hair salon. Well, how do you layer? And then it became too heavy, and then I had to cut through and figure out. Everything became an invention because I got stuck. I was working my way out of a bad situation.”

Ghosts of figuration

Then, Bradford began using paper he found on the street: layers of posters, discarded flyers and other ephemera. When soaked in water, this material transformed, creating diverse color effects. Meanwhile, the paper material held a symbolic charge carried over from its past life. Bradford’s form of abstraction is animated by the ghosts of figuration.

To Liquefy the paper

He explains: “When I was pulling the paper down from, let’s say, the street, and when I had the paper in my studio, I needed to liquefy it. I needed to have movement in the paper. So I started wetting it. And once you wet paper, it kind of loosens. And once it loosens you can actually manipulate it like paint. I don’t use the information as much. It’s almost like I’m turning the information inside and really using it through abstraction.”

To appreciate is to support.

To support is to donate.

Support JB Reports by becoming a sustaining Patron with a recurring or a spontaneous donation.

Sam Bardaouil

In the most striking room of the Berlin exhibition, all the art is on the floor. You trample it underfoot. Its irregular surface, made from an accumulation and agglomeration of various papers, stretches out without end. This is “Float.” Sam Bardaouil, co-curator and co-director of the museum, described it as a painting-sculpture.

Giant protuberance

Another impressive work, “Spoiled Foot,” consists of a giant, round protuberance made of an indescribable, colorful material that, in spite of what the title implies, hangs down from the ceiling, partially obstructing the way. It’s as if a sickly soil had, up in the sky, sprouted a menacing growth. The title might suggest a gait hindered by a diseased foot—or something else altogether.

Mark, what are you digging for?

Moving from one room to another in the exhibit, you might find yourself repeating, like a mantra: What you see is not what you think it is. The artist comments: “I’m a Scorpio, so everything’s hidden…I’m digging, I’m digging. I’m saying, ‘Mark, what are you digging for?’ I say, ‘Well, I don’t know. But I have to dig. Maybe I need to excavate some of it to get to something lighter.’”

School saved him

Reflecting on his early years, Bradford adds: “Going to school really saved my life. Going to art school and meeting these interesting people who were creative—I never see these people before because I was so much in the streets. I was only putting one foot in front of the other and trusting my instincts. It was never a strategy for anything. Whatever I felt strongly about, is what I did.”

Meeting Mark Bradford, one of the first things that strikes you is his radiant smile, his seemingly jovial demeanor. But in his nature, he is deeply serious.

What you see is not what you would think it is.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.