The greatest artists present us with endless opportunities to discover new sides to their work.

A perfect example is at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel, Switzerland, where 62 paintings by Claude Monet are currently on display.

The thematic hanging and the choice of works hones in on a 25-year period from 1880, when the painter liberated himself from what might be termed the impressionist dogma, until 1905 when he was pursuing an increasingly bold style of painting, closer to abstraction, and which drew inspiration from his garden, particularly his cherished lily pond (nympheas). Between these dates, Monet was frequently exploring, and would set the stage for modern art in magisterial fashion.

On first impressions this new show offers an immense feast for the eye.

Eschewing chronology, the paintings are instead organised by theme.

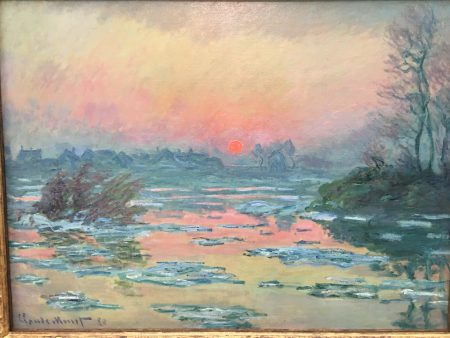

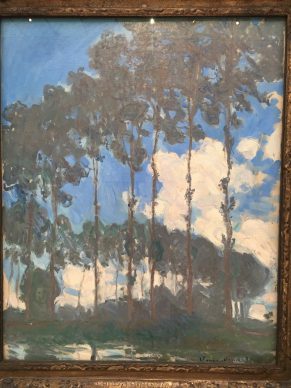

The gaze is drawn initially to all those gentle and infinitely harmonious compositions that play with colours and effects of light: from the water’s edge after a flood at Giverny in 1896, or the poplar trees in spring in a bright green field in 1894, and a purple haystack against the sky in 1891.

The show’s curator, Ulf Küster, explains how Monet used a studio boat that he could even sleep in, and which helped him to plumb nature’s depths from the surface of the water.

He reveals the idea behind the exhibition:

But next to these masterpieces, which deliver immediate pleasure, the exhibition also offers what appear to be more banal paintings.

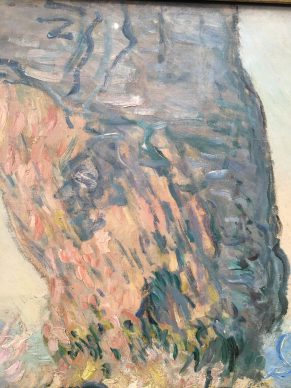

You really need to look at the canvases up close. The exhibition forces you to open your eyes to truly understand Monet’s genius.

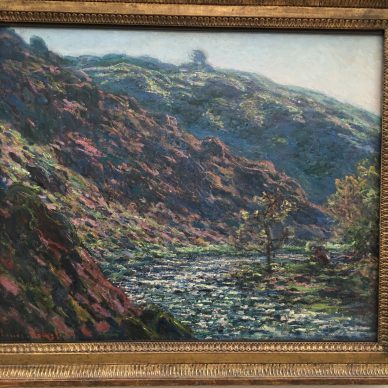

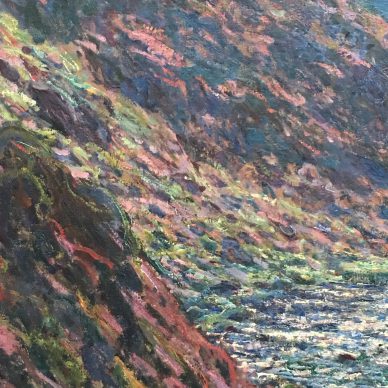

-The gloomy mountain view ‘Ravine of the Petite Creuse’ (1889) is a close cousin of certain landscape paintings by Giovanni Segantini, the remarkable Italian master of post-impressionism. The hill is composed of an infinite number of strands of colours, flicked with the brush to produce effects of light. Monet varies greasy strokes (using more oil in the paint) and dry ones to create the impression of movement or matter.

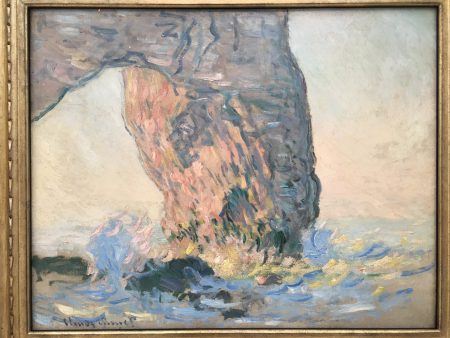

– His ‘Waves at the Manneporte’ (1885) appears to represent, through an infinitude of lively gestures, the leg of a giant formed out of the rocks, among the waves. It’s not a far cry from Georg Baselitz‘s stroke.

– ‘The Poplars’ (1891), aligned geometrically, bring to mind the forests painted by Piet Mondrian before he embraced abstraction.

-His ‘Smoke in the Fog’ at Charing Cross (1902), a noticeably urban scene, oddly resembles his final Nympheas paintings, diluted in hazy landscapes.

Ulf Küster talks about what is generally interpreted as abstraction in Monet’s work:

‘Morning on the Seine’ (1897), a work which blends trees, reflections, sky and water, without us knowing exactly where is the top or the bottom of the composition, is without question the masterpiece of the exhibition. Monet is at the height of his mastery of illusion.

He creates that powerful sense of unease in the face of extreme beauty.

Until 25 May. www.fondationbeyeler.ch/fr.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.