Ouro Preto.

Perched on a cluster of slippery hills is a city of white, blue and gold, of sloping streets paved in large rough-edged stones, of fountains and churches, of rockeries, of Jesus and Mary.

We’re in Brazil, in the state of Minas Gerais (‘the General Mines’), a five-hour drive from Rio de Janeiro and 165 km far from the first airport.

The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, who committed suicide in Brazil, discovered Ouro Preto, speaking of it as being like ‘Toledo, Venice, Salzburg, the Aigues-Mortes of Brazil.’

In the 20s another illustrious man of letters, the poet Blaise Cendrars, travelled to Brazil on three separate occasions and in 1924 discovered this extraordinary corner of the world accompanied by the excellent Brazilian modern painter and one-time student of Fernand Léger, Tarsila do Amaral (Moma New York has a retrospective of her work from 11 February 2018).

Blaise Cendrars was planning to write a book about Aleijadinho, the hero of this 18th century city.

Since I first visited Ouro Preto some eighteen years ago, and on various occasions since that first visit, I too wanted to write a book.

Blaise Cendrars sold the idea to his publisher but never got around to writing it.

He confessed to Henry Miller that he was too lazy to undertake the project.

I was scared of following in his footsteps.

Despite the illness and subsequent passing of my publisher, the remarkable Xavier Douroux from Les Presses du Réel in June of this year, one of the few people in France who knew about Aleijadinho, the book has finally seen the light of day in french (photos in the book by Aurore Belkin), with the title ‘Aleijadinho, le Brésil est un sculpteur métisse’ (‘Aleijadinho. Brazil is a mixed-race sculptor’).

And it’s only after this event that I was able to return to Ouro Preto.

I had acquitted myself of my task.

This is a short walk thorough this town now listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I recommend to all lovers of the beautiful: make an effort to visit Ouro Preto.

Everywhere you turn, you see arresting landscapes completely intact since the 18th century. This is because at the end of the 19th century, the Mineiro government decided to transfer the state capital to a new city, Belo Horizonte, where scientific progress could blossom far from the mountains which hampered expansion and the forward march of modernity.

Ouro Preto was therefore left in its sublime ‘sauce’, and with it the legend of Aleijadinho, a national icon in Brazil but completely unknown abroad.

Aleijadinho (his real name is Francisco Lisboa,probably 1738-1814) is an affectionate sobriquet as Brazilians are so fond of bestowing on their illustrious men.

Aleijadinho, or ‘the little cripple’, died of a degenerative disease which progressively deprived him of the use of his members and deformed his face.

In Brazil his legacy is akin to Victor Hugo’s for exemple in France. In other words, almost everyone knows who Aleijadinho is even if they are not necessarily familiar with his work.

The story of Aleijadinho is sublime on two accounts.

Firstly because he was an artist with a truly exceptional body of work and secondly because he was a black artist (the son of an African slave and a Portuguese architect) who achieved fame in the 18th century.

Several conditions were propitious for his artistic blossoming.

Ouro Preto grew out of the discovery and the exploitation of colossal amounts of gold over a 70-year period which irrigated the Portuguese empire.

As a result, it was necessary to thank God by building churches locally.

In Ouro Preto even slaves had their own magnificent church, Nossa Senhora do Rosário, a building full of curves that can still be visited every afternoon.

The new Brazilian society was the product of intense mixing, ‘miscegenation’ as the experts call it.

The Portuguese came as bachelor conquerors and it was therefore imperative to occupy the vast country.

Their illegitimate dark children would obtain some degree of recognition.

Nothing like this could have happened in the United States, for example.

Recall, however, that slavery was only abolished in Brazil in 1888.

The work of Aleijadinho encompassed architecture and above all sculpture. It is often situated in the catch-all Baroque category.

But he in fact had three distinct periods.

The first was a style still searching for itself, the second was a confounding virtuosity mainly influenced by Portuguese Baroque, and the third an expressionist desire in three dimensions, undoubtedly influenced by the state of his health and also by African art probably.

Over time the identity of Aleijadinho, whose biography has various grey areas, was recuperated (the word did not have negative connotations in a country looking to forge its identity) by different Brazilian causes, which looked to identify themselves with a genius-like hero who was the product of racial mixing.

The most striking testaments to his sculptural work in the city if his birth are found in the beautiful Museum of the Inconfidencia.

But he also designed in Ouro Preto the architecture of one of the most sublime churches in this great country,

São Francisco de Assis.

Behind this rococo temple is a mini Aleijadinho museum containing several of his sculptures.

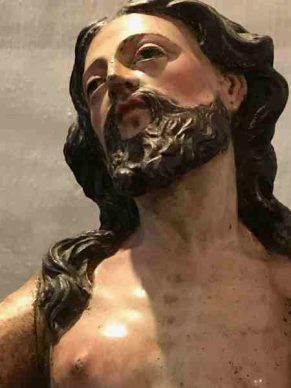

Finally, true fans have to visit Congonhas, a mining town a little over an hour’s drive away, which is home to a sanctuary at the summit of a hill comprising of several pavilions in which lie the final work of the great Aleijadinho: sixty four life-sized characters sculpted in cedar wood and painted, and which reconstruct the scenes of the passion of Christ.

It’s beggars belief.

At the summit of the hill Aleijadinho also choreographed a kind of dance of the prophets, cut from stone, and which welcome the visitor.

The French photographer Marcel Gautherot (1910-1996) sublimely captured them for posterity in the 40s.

In Rio there is currently an exhibition of his work at the Paço Imperial.

In 1963, the one-time head curator of the Louvre, Germain Bazin (1901-1998) published the first scientific study of Aleijadinho’s work. And in Brazil he has not been forgotten.

In these times of horrendous racism across the board, it is well worth exploring the story of a man who was born a slave and who would haul himself up to the summit of Brazilian art.

All the photos in this post have been taken by JBH during her recent stay in Ouro Preto. Aurore Belkin is the author of all the photos in the book ‘Aleijadinho, le Brésil est un sculpteur métis’.

Aleijadinho, le Brésil st un sculpteur métis. Les Presses du réel.

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.